On the chart shown you can consider several things. (To view the chart, click on the thumbnail image. Use the back arrow on your browser to return to this page.)

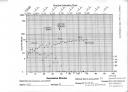

The attached chart shows data from March 29, 1984 that I had originally charted on a "converted" daily Standard Celeration Chart (DC-9EN). I was 28 at the time. Back then I was testing out how to obtain a Learning Picture in a half hour or so.

There were no "timings charts" back then, so I had used a daily chart, crossing out the word "Days" on the x-axis label and replacing it with minutes. (That original chart is not shown here).

The chart shown here represents an example application of the Merbitz & Layng (1996) V010396 Sprint #19 "Successive Minutes" chart. Across the bottom axis are successive real-time minutes, not days, not sessions, and not successive timings. I found the old chart from 1984 today and recharted its data onto the Merbitz & Layng today. It took only a few minutes to do so.

To read the chart, up the left scale is Responses per Minute. Across the bottom scale is Successive Minutes. The y-axis up the left is a multiply-divide scale. The x-axis across the bottom is an add-subtract scale.

What this is a chart of is of me doing one-minute timings of SAFMEDS (Say All Fast a Minute Every Day Shuffled; in this case, a Minute Every Other Minute Shuffled). I ran the timings every other minute. In some cases, two minutes elapsed between timings. But, these data were charted in real time, so when one minute elapses between timings, the time line is blank, and when two minutes elapsed between timings, two time lines in succession are blank. During the minute in between timings I would count the corrects and incorrects, chart them quickly, and then reshuffle the cards. The round dots are corrects per minute and the x's are incorrects per minute. I drew in Record Floors down at the 1 line.

The topic was Apple II Machine Language terms, which I had made into SAFMEDS. At the time I was learning how to program computers, and I was thinking about learning machine language. I was not doing this for any class, job, or formal project. Just learning it on my own.

On the chart are a couple of event manipulations. About 20 minutes into the study session, I decided to study the errors during the one minute between timings, because there were four to eight errors that still persisted (cards that seemed difficult to learn). And about 38 minutes into the session, I set an aim goal of 40 per minute (but not an actual aim-star, which would include not only the frequency level, but also the time line. I put the aim over onto the y-axis).

Overall, the chart shows a "jaws" learning picture across a 70 minute period of time. Over that period I did 34 one-minute timings. There was a slight crossover picture at the start, but only two times when errors were above corrects, so to me this LP looks more like a "jaws" than a "crossover jaws" picture.

Some implications:

Last year I discussed on the Standard Celeration listserve the question of charting data in real time, but did not have the ability at the time to put up successive minutes real-time charted data to illustrate the point. While the attached data are from an old chart, they illustrate HOW the Merbitz & Layng real-time Successive Minutes chart could be used to work with minute-by-minute types of recording.

You can do more than the "traditional" four or five timings within a day (since when did that become an actual tradition? Why? On what basis?). When doing timings within a daily session of time, it could be, as this chart illustrates, possible to do many timings.

There are limits. On the chart I noted that at about 67 to 68 minutes into doing this session that I was fatiguing. So, I wouldn't necessarily recommend doing such an extensive session with yourself or with a learner for that and possibly for other reasons. On the other hand, you might try doing 10 to 15 to maybe 20 timings within a day if that is logistically feasible, and record them in real time.

The Merbitz & Layng chart is calibrated, I found out by using a BRCo CFM-4 Celeration Finder, to the proper x2 34 degree angle. I wrote in some celeration values covering some periods of the session (e.g., an initial x2.3 celeration of corrects, followed by a x1.3 midway through and a x1.1 during the fatiguing). The celeration period of this chart is a 10-minute period of time, so technically the first celeration would be stated as x2.3 per minute per 10 minutes (celeration = count per time per time).

The image is slightly angled. I tried relining up the page in the scanner a couple of times, but still it was angled off a tad. Then, I measured the margins of the paper, and the distance from edge of paper to the frame was not the same going across. The copies of the Merbitz & Layng chart that I have seem to have been xeroxed. That goes to another point that Dr. Og Lindsley made in his last-ever talk at the 2003 IPTC about chart standards, that one of the standards is the margins. Og was very precise and adamant about this. Margins had to be exact in order to function towards exact overlays, but this slight-angledness now also seems to be another reason why margin standards need to be actual standards as he said.

— JE

REFERENCE:

Lindsley, O.R. (2003). Precision Teaching's eyes and ears: Standard Celeration Charts and terms. Invited Address presented at the International Precision Teaching Conference, Columbus, OH 6 Nov 2003.